Welcome back to our blog series “Have You Watched a Good Book Lately?” The series’ intention is to track a number of books’ progression from the printed page to the silver screen and assess how well or how badly the filmmakers accomplished each of the adaptations.

Today we’re going to be discussing “Killings,” a short story written by Andre Dubus and first published in The Sewanee Review in 1979. It was adapted for the screen in 2001 as “In the Bedroom” by screenwriters Rob Festinger and Todd Field and was directed by Field (“Little Children”). For those of you unfamiliar with the basic premise, here is a brief synopsis of the short story and the movie (adapted from eNotes.com):

“In a seemingly idyllic small New England town, Matt and Ruth Fowler struggle to come to terms with the murder of their son, Frank. Frank’s murderer, Richard Strout, lives in town while awaiting trial. Convinced that Richard won’t receive an adequate jail sentence, Matt decides to take matters in his own hands.”

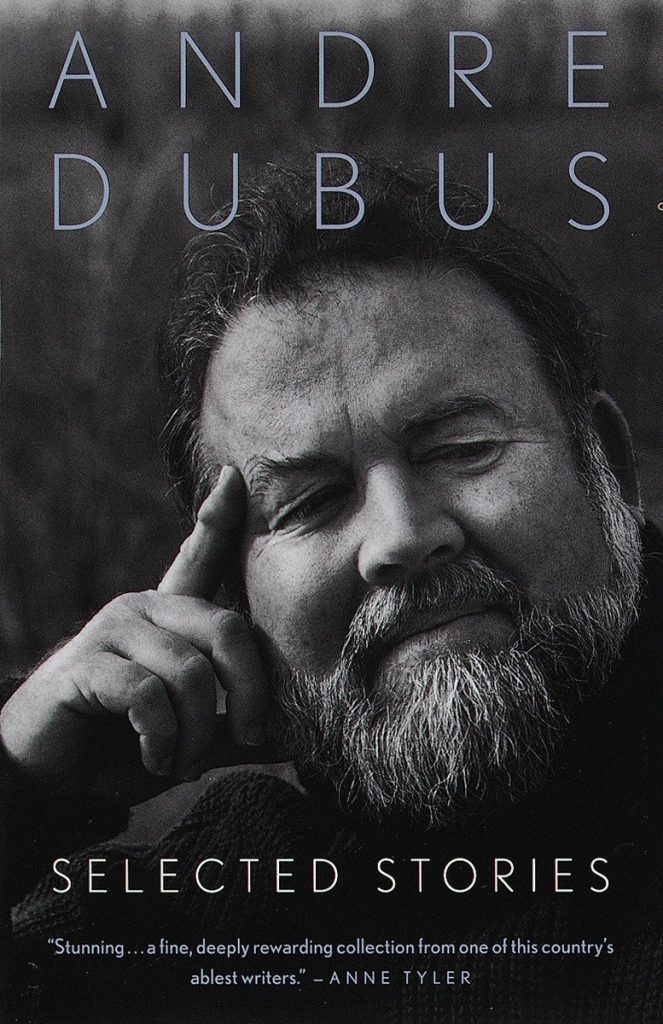

Andre Dubus

From the Source’s Mouth

Let’s start our discussion with one of the main concerns of any story adaptation – how true is the film to the source material? There is no question that “In the Bedroom” draws heavily from “Killings” for its main plot, but it diverges in a number of other ways that are sometimes interesting and sometimes quite puzzling.

“Killings” tells a story of powerful and sometimes dangerous emotions – of overwhelming grief, despair, and unchecked rage. It opens as Matt Fowler and his wife Ruth are burying their youngest child, Frank, in a small town at the edge of the sea near Boston. After a month of seclusion, Ruth tells Matt to accept his friend Willis’ invitation for a poker game, since “he [can’t] sit home with her for the rest of his life.” After the game breaks up, he stays behind to talk with Willis. The conversation quickly turns to what has happened. They mention none of the specifics, however – they have a shared understanding that we, the reader, haven’t yet obtained. It lends an air of mystery to both what took place and to the discussion itself, and we feel compelled to turn the pages to learn more. “How often have you thought about it?” Willis asks him. “Every day since he got out. I didn’t think about bail. I thought I wouldn’t have to worry about him for years.” It also bothers Matt that “he” is free to walk around town, and Ruth is distressed every time she sees “him.”

“I’ve got a .38 I’ve had for years. I take it to the store now,” Matt tells Willis. “I tell Ruth it’s for the night deposits, but “she knows I started carrying it after the first time she saw him in town. She knows it’s in case I see him, and there’s some kind of a situation –“

I’ve got a .38 I’ve had for years. I take it to the store now.

We’re busting to know the details at this point, and Dubus finally starts giving us the backstory. “He” is Richard Strout, a one-time college athlete who dabbled in his father’s construction business before marrying a young girl named Mary Ann and becoming a bartender. He has a reputation for fighting and drinking and being perpetually sullen. Frank became involved with Mary Ann shortly after she obtained a separation from Richard. He met her on the beach where he was lifeguarding for the summer before heading to an economics graduate program. He spent the days with her and her two boys on the beach, and many evenings – and nights – at her house. One day Richard came by, though, and he beat Frank up for “making it with his wife.”

Ruth didn’t like that Frank was seeing Mary Ann in the first place – she was in the process of a divorce, she had two children, and she was four years older than him. And, she confessed to Matt, she had heard the rumors that the marriage had soured early as both parties were having affairs. Matt, though, was so smitten himself with Mary Ann that he didn’t see the problems. She was tanned and pretty, he enjoyed talking and laughing with her when she was at their house, and he fantasized about her when she wasn’t. And her eyes had the shadow of a pain that touched him, probably from the breakup. He thought the divorce was a sign that she was moving on. And while Frank hadn’t really entertained the idea of marriage, Matt suggested that, despite the huge responsibility it would entail, he wouldn’t be opposed.

Then one day, “Richard Strout shot Frank in front of the boys. [He] came in the front door and shot Frank twice in the chest and once in the face with a 9 mm automatic. Then he looked at the boys and Mary Ann, and went home to wait for the police.” From the time that Mary Ann called Matt to tell him what happened until the present, a Saturday night in September, he goes through the motions of life but does not live it. And “beneath his listless wandering, every day in his soul he shot Richard Strout in the face.” And so Dubus brings us to the painful, bleeding heart of his narrative.

He came in the front door and shot Frank twice in the chest

Matt and Willis drive up to the bar in the next town over where Richard now works and wait for all the customers to leave. As Richard locks up, they approach him with guns drawn. They force him into his car and tell him to drive to his house without attracting attention. Matt tells Richard to pack a suitcase with clothes for warm weather. “What’s going on?” Richard asks him. “You’re jumping bail,” Matt responds tersely. As he looks around the house, he sees a picture of Mary Ann on the wall. “He recalled her eyes, the pain in them, and he was conscious of the circles of love he was touching with the hand that held the revolver so tightly now,” Dubus writes eloquently. Richard pleads with him, telling him he’s going to be put away for 20 years so why do this, but Matt won’t listen. “It’s the trial,” he says. “We can’t go through that, my wife and me. So you’re leaving.”

They drive for a long time, to a desolate part of the woods – someone will be hiding Richard until it’s safe for him to travel. When they arrive, Strout suspects the worst and tries to make a run for it, but Matt shoots him in the stomach. Falling, he tries to crawl away, but Matt comes up behind him and shoots him again, this time in the head. Matt and Willis dump the case and Richard’s body into the hole they had planned after the game and dug the week before and carefully cover all traces of blood on the ground. Throwing the gun into the nearby lake, they drive down to Boston, where they leave Richard’s car. Matt arrives home as the sun breaks the horizon, and Ruth is waiting. “Did you do it? Are you all right?” “I think so,” he answers, and, cradled in her arms, he tells her everything he did to try to make the world right for them again, sobbing with both grief and relief.

They drive for a long time, to a desolate part of the woods.

The film, “In the Bedroom,” follows Matt’s same basic character arc, but there are some trivial – and a number of substantial – changes. We don’t start with the funeral; instead, the film explores the relationship between father and son, which I have to admit leads to more of an emotional investment for the viewer. Matt is the town doctor, but he spends most of his lunch hours with Frank because “I want to be with my son.” The setting is a small seaside town in Maine, not Massachusetts, probably because it was easier for the filmmakers to get permits to shoot there. Fishing is the primary industry, and Strout’s is the main cannery operating in the area. Frank is working on a fishing boat for the summer before he heads off to college to become an architect, not go into economics. He loves designing and building things, but he also loves the sea and considers becoming a fisherman like his grandfather. The title refers to lobster fishing. The traps are built with a space called “the bedroom” that has an opening designed to let the lobsters get in but not to get out. If more than two lobsters end up in the bedroom, usually they start to fight, and may lose claws in the process. The foreshadowing of “three’s a crowd” could not be more evident.

Unlike in the book, Frank is an only child, which makes what happens that much more tragic for his parents. He has been involved with Natalie (the filmmakers changed Mary Ann’s name for some reason) for a short time, but he clearly enjoys her presence, and he gets on wonderfully with her two boys. Ruth is against the relationship while Matt is supportive, for all the same reasons as described in the story. While Frank is on the phone with a college recruiter, he gets a panicked call from one of Natalie’s children. He races over to her house, which has been completely trashed. Apparently Richard stopped by and got angry about her going out with Frank, but she chased him off. While Frank is there, though, Richard returns, pounding on the door and demanding to be let in. Frank sends both Natalie and the boys upstairs while he confronts an increasingly angry Richard, who now has a gun. While Frank pleads with him to leave, Richard’s rage explodes, and he shoots Frank directly in the face. Natalie, hearing the shot, rushes downstairs to find Frank dead on the floor.

After the funeral…

After the funeral, Matt and Ruth attend the bail hearing, which the judge also wants to use as a probable cause hearing; that means he’ll hear witnesses in the case. Natalie is a wreck on the stand. The prosecutor, though, is all over her. “Let me get this straight – you heard the shot? Didn’t you say in the initial police report that you saw him firing the gun?” Stricken, Natalie can’t dig herself out of the hole she’s created for herself and for the case. Richard makes bail, and the trial the attorney said shouldn’t be any later than that October is pushed back a year to 18 months, leaving Ruth and Matt devastated.

Building on grief and anger, tensions between the couple escalate. One day, Ruth explodes at Matt about his going out with his buddies, which, in the film, she hadn’t suggested. “What do you want from me?” he demands. “I want you not to act like nothing happened. You have no feelings! You want to reason through everything – you gave that to Frank. You let him get away with everything, that’s why he always came to you for help.” But Matt’s not having it. “You know why he didn’t come to you? Because you were always so controlling, so distant and overbearing. Everything he did was wrong. You’ve become so bitter, it scares me.” I believe this dramatic confrontation, while not in the original story, is very important in establishing the depth of the characters and showing how their relationship has changed due to circumstance; as such, it was important to add to the film.

Finally calming down, Ruth confides in Matt that every time she goes into town she sees Richard walking about, smiling, laughing, and free, and it distresses her greatly. Realizing that Richard probably won’t get more than five years for manslaughter because of Natalie’s testimony and his own claims that the shot came from a scuffle, Matt goes to talk to Willis, and the remainder of the film proceeds as it does in the story.

Non-Standard Deviations

Though there were a number of other deviations from the original story, the one that sticks out the most is that, in the film, Richard did not shoot Frank in front of the boys. That would have been an incredibly traumatic experience for them, and the writers would have had to add scenes where those consequences were addressed. Those scenes would have only served to bloat the story and to detract from the main arc in ways that would not serve the film as a whole.

Book or film – film or book. Which will we prefer?

The Final Cut

So, how did “In the Bedroom” as a movie fare as a story adaptation overall? Reasonably well. The filmmakers made some substantial changes, but, as a whole, they added to the telling. I would give the film a B+ for a sensitive handling of the material.

What do you think? Do you agree? Disagree? Please add your comments in the section below.

– Miriam Ruff, Content Creator, PoetsIN

DISCLAIMER: The opinions discussed in this blog post are solely those of the blogger and do not necessarily represent any thoughts, values, or opinions of PoetsIN and any of its affiliate groups.

Please follow and like us:

Welcome back to our blog series “Have You Watched a Good Book Lately?” The series’ intention is to track a number of books’ progression from the printed page to the silver screen and assess how well or how badly the filmmakers accomplished each of the adaptations.

Today we’re going to be discussing “Killings,” a short story written by Andre Dubus and first published in The Sewanee Review in 1979. It was adapted for the screen in 2001 as “In the Bedroom” by screenwriters Rob Festinger and Todd Field and was directed by Field (“Little Children”). For those of you unfamiliar with the basic premise, here is a brief synopsis of the short story and the movie (adapted from eNotes.com):

“In a seemingly idyllic small New England town, Matt and Ruth Fowler struggle to come to terms with the murder of their son, Frank. Frank’s murderer, Richard Strout, lives in town while awaiting trial. Convinced that Richard won’t receive an adequate jail sentence, Matt decides to take matters in his own hands.”

Andre Dubus

From the Source’s Mouth

Let’s start our discussion with one of the main concerns of any story adaptation – how true is the film to the source material? There is no question that “In the Bedroom” draws heavily from “Killings” for its main plot, but it diverges in a number of other ways that are sometimes interesting and sometimes quite puzzling.

“Killings” tells a story of powerful and sometimes dangerous emotions – of overwhelming grief, despair, and unchecked rage. It opens as Matt Fowler and his wife Ruth are burying their youngest child, Frank, in a small town at the edge of the sea near Boston. After a month of seclusion, Ruth tells Matt to accept his friend Willis’ invitation for a poker game, since “he [can’t] sit home with her for the rest of his life.” After the game breaks up, he stays behind to talk with Willis. The conversation quickly turns to what has happened. They mention none of the specifics, however – they have a shared understanding that we, the reader, haven’t yet obtained. It lends an air of mystery to both what took place and to the discussion itself, and we feel compelled to turn the pages to learn more. “How often have you thought about it?” Willis asks him. “Every day since he got out. I didn’t think about bail. I thought I wouldn’t have to worry about him for years.” It also bothers Matt that “he” is free to walk around town, and Ruth is distressed every time she sees “him.”

“I’ve got a .38 I’ve had for years. I take it to the store now,” Matt tells Willis. “I tell Ruth it’s for the night deposits, but “she knows I started carrying it after the first time she saw him in town. She knows it’s in case I see him, and there’s some kind of a situation –“

I’ve got a .38 I’ve had for years. I take it to the store now.

We’re busting to know the details at this point, and Dubus finally starts giving us the backstory. “He” is Richard Strout, a one-time college athlete who dabbled in his father’s construction business before marrying a young girl named Mary Ann and becoming a bartender. He has a reputation for fighting and drinking and being perpetually sullen. Frank became involved with Mary Ann shortly after she obtained a separation from Richard. He met her on the beach where he was lifeguarding for the summer before heading to an economics graduate program. He spent the days with her and her two boys on the beach, and many evenings – and nights – at her house. One day Richard came by, though, and he beat Frank up for “making it with his wife.”

Ruth didn’t like that Frank was seeing Mary Ann in the first place – she was in the process of a divorce, she had two children, and she was four years older than him. And, she confessed to Matt, she had heard the rumors that the marriage had soured early as both parties were having affairs. Matt, though, was so smitten himself with Mary Ann that he didn’t see the problems. She was tanned and pretty, he enjoyed talking and laughing with her when she was at their house, and he fantasized about her when she wasn’t. And her eyes had the shadow of a pain that touched him, probably from the breakup. He thought the divorce was a sign that she was moving on. And while Frank hadn’t really entertained the idea of marriage, Matt suggested that, despite the huge responsibility it would entail, he wouldn’t be opposed.

Then one day, “Richard Strout shot Frank in front of the boys. [He] came in the front door and shot Frank twice in the chest and once in the face with a 9 mm automatic. Then he looked at the boys and Mary Ann, and went home to wait for the police.” From the time that Mary Ann called Matt to tell him what happened until the present, a Saturday night in September, he goes through the motions of life but does not live it. And “beneath his listless wandering, every day in his soul he shot Richard Strout in the face.” And so Dubus brings us to the painful, bleeding heart of his narrative.

He came in the front door and shot Frank twice in the chest

Matt and Willis drive up to the bar in the next town over where Richard now works and wait for all the customers to leave. As Richard locks up, they approach him with guns drawn. They force him into his car and tell him to drive to his house without attracting attention. Matt tells Richard to pack a suitcase with clothes for warm weather. “What’s going on?” Richard asks him. “You’re jumping bail,” Matt responds tersely. As he looks around the house, he sees a picture of Mary Ann on the wall. “He recalled her eyes, the pain in them, and he was conscious of the circles of love he was touching with the hand that held the revolver so tightly now,” Dubus writes eloquently. Richard pleads with him, telling him he’s going to be put away for 20 years so why do this, but Matt won’t listen. “It’s the trial,” he says. “We can’t go through that, my wife and me. So you’re leaving.”

They drive for a long time, to a desolate part of the woods – someone will be hiding Richard until it’s safe for him to travel. When they arrive, Strout suspects the worst and tries to make a run for it, but Matt shoots him in the stomach. Falling, he tries to crawl away, but Matt comes up behind him and shoots him again, this time in the head. Matt and Willis dump the case and Richard’s body into the hole they had planned after the game and dug the week before and carefully cover all traces of blood on the ground. Throwing the gun into the nearby lake, they drive down to Boston, where they leave Richard’s car. Matt arrives home as the sun breaks the horizon, and Ruth is waiting. “Did you do it? Are you all right?” “I think so,” he answers, and, cradled in her arms, he tells her everything he did to try to make the world right for them again, sobbing with both grief and relief.

They drive for a long time, to a desolate part of the woods.

The film, “In the Bedroom,” follows Matt’s same basic character arc, but there are some trivial – and a number of substantial – changes. We don’t start with the funeral; instead, the film explores the relationship between father and son, which I have to admit leads to more of an emotional investment for the viewer. Matt is the town doctor, but he spends most of his lunch hours with Frank because “I want to be with my son.” The setting is a small seaside town in Maine, not Massachusetts, probably because it was easier for the filmmakers to get permits to shoot there. Fishing is the primary industry, and Strout’s is the main cannery operating in the area. Frank is working on a fishing boat for the summer before he heads off to college to become an architect, not go into economics. He loves designing and building things, but he also loves the sea and considers becoming a fisherman like his grandfather. The title refers to lobster fishing. The traps are built with a space called “the bedroom” that has an opening designed to let the lobsters get in but not to get out. If more than two lobsters end up in the bedroom, usually they start to fight, and may lose claws in the process. The foreshadowing of “three’s a crowd” could not be more evident.

Unlike in the book, Frank is an only child, which makes what happens that much more tragic for his parents. He has been involved with Natalie (the filmmakers changed Mary Ann’s name for some reason) for a short time, but he clearly enjoys her presence, and he gets on wonderfully with her two boys. Ruth is against the relationship while Matt is supportive, for all the same reasons as described in the story. While Frank is on the phone with a college recruiter, he gets a panicked call from one of Natalie’s children. He races over to her house, which has been completely trashed. Apparently Richard stopped by and got angry about her going out with Frank, but she chased him off. While Frank is there, though, Richard returns, pounding on the door and demanding to be let in. Frank sends both Natalie and the boys upstairs while he confronts an increasingly angry Richard, who now has a gun. While Frank pleads with him to leave, Richard’s rage explodes, and he shoots Frank directly in the face. Natalie, hearing the shot, rushes downstairs to find Frank dead on the floor.

After the funeral…

After the funeral, Matt and Ruth attend the bail hearing, which the judge also wants to use as a probable cause hearing; that means he’ll hear witnesses in the case. Natalie is a wreck on the stand. The prosecutor, though, is all over her. “Let me get this straight – you heard the shot? Didn’t you say in the initial police report that you saw him firing the gun?” Stricken, Natalie can’t dig herself out of the hole she’s created for herself and for the case. Richard makes bail, and the trial the attorney said shouldn’t be any later than that October is pushed back a year to 18 months, leaving Ruth and Matt devastated.

Building on grief and anger, tensions between the couple escalate. One day, Ruth explodes at Matt about his going out with his buddies, which, in the film, she hadn’t suggested. “What do you want from me?” he demands. “I want you not to act like nothing happened. You have no feelings! You want to reason through everything – you gave that to Frank. You let him get away with everything, that’s why he always came to you for help.” But Matt’s not having it. “You know why he didn’t come to you? Because you were always so controlling, so distant and overbearing. Everything he did was wrong. You’ve become so bitter, it scares me.” I believe this dramatic confrontation, while not in the original story, is very important in establishing the depth of the characters and showing how their relationship has changed due to circumstance; as such, it was important to add to the film.

Finally calming down, Ruth confides in Matt that every time she goes into town she sees Richard walking about, smiling, laughing, and free, and it distresses her greatly. Realizing that Richard probably won’t get more than five years for manslaughter because of Natalie’s testimony and his own claims that the shot came from a scuffle, Matt goes to talk to Willis, and the remainder of the film proceeds as it does in the story.

Non-Standard Deviations

Though there were a number of other deviations from the original story, the one that sticks out the most is that, in the film, Richard did not shoot Frank in front of the boys. That would have been an incredibly traumatic experience for them, and the writers would have had to add scenes where those consequences were addressed. Those scenes would have only served to bloat the story and to detract from the main arc in ways that would not serve the film as a whole.

Book or film – film or book. Which will we prefer?

The Final Cut

So, how did “In the Bedroom” as a movie fare as a story adaptation overall? Reasonably well. The filmmakers made some substantial changes, but, as a whole, they added to the telling. I would give the film a B+ for a sensitive handling of the material.

What do you think? Do you agree? Disagree? Please add your comments in the section below.

– Miriam Ruff, Content Creator, PoetsIN

DISCLAIMER: The opinions discussed in this blog post are solely those of the blogger and do not necessarily represent any thoughts, values, or opinions of PoetsIN and any of its affiliate groups.

admin