Welcome a Halloween special of our series of “Have You Watched a Good Book Lately?”

The series’ intention is to track a number of books’ progression from the printed page to the silver screen and assess how well or how badly the filmmakers accomplished each of the adaptations.

One of the many Pit and the Pendulum book cover

Today we’re going to be discussing “The Pit and the Pendulum,” a short story written by Edgar Allen Poe first published in 1842 in the literary annual The Gift: A Christmas and New Year’s Present for 1843 and adapted for the screen in 1961 as “Pit and the Pendulum” by famed science fiction and horror writer Richard Matheson and “B”-film director Roger Corman (414 producer credits and 56 directorial credits). It has been adapted for film a number of other times, but for the purposes of this blog, we will be looking at the 1961 Corman version. For those of you unfamiliar with the basic premise, here is a brief synopsis of the short story (adapted from Wikipedia) and the film (taken from imdb.com):

“An unnamed prisoner of the Spanish Inquisition, convicted of an unspecified crime, explicitly describes his experience of being tortured. The story is especially effective at inspiring fear in the reader because of its heavy focus on the senses, such as sound, which imbued a sense of reality, unlike many of Poe’s other stories which are aided by the supernatural. It should be noted that, while the events are horrifying, Poe did take numerous liberties with historical facts while writing the story.”

“In the sixteenth century, Francis Barnard travels to Spain to clarify the strange circumstances of his sister’s death after she had married the son of a cruel Spanish Inquisitor.”

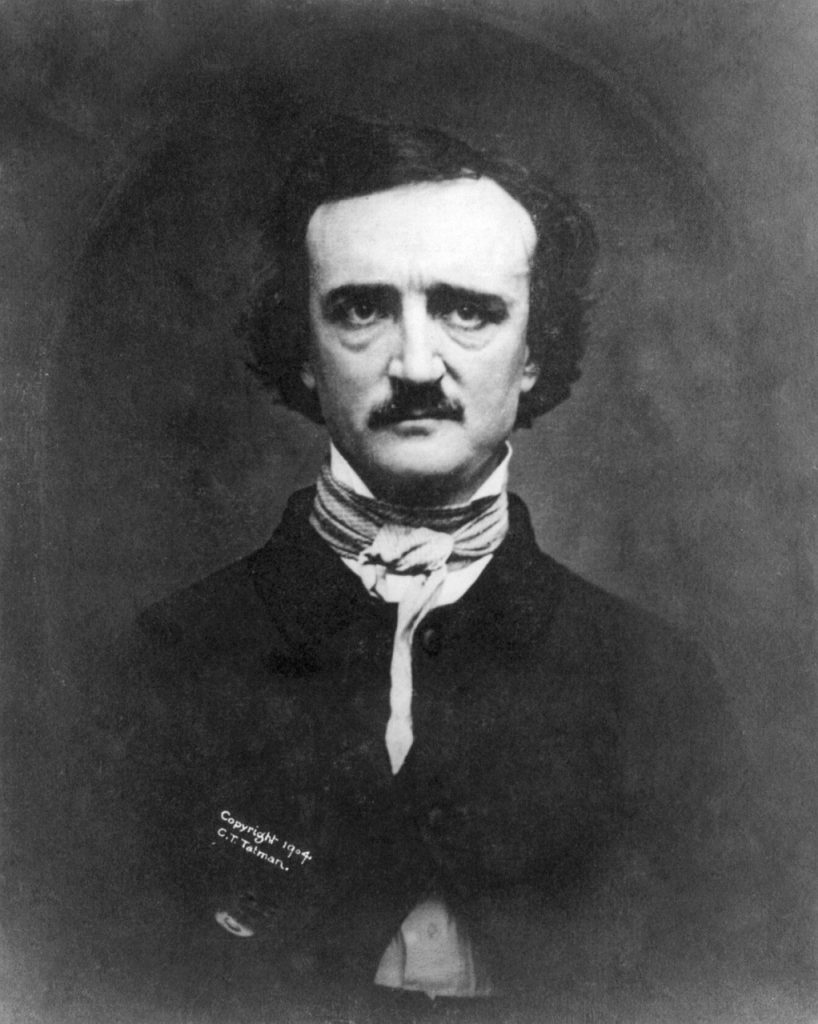

Our old friend Poe

From the Source’s Mouth

Let’s start our discussion with one of the main concerns of any story adaptation – how true is the film to the source material? Well, both the story and the film refer to the Spanish Inquisition (though that event occurred before the time period in which the film was set), and both do contain a pit and a pendulum somewhere along the line, but that’s about where the similarity ends. It’s a shame, as the original story, awash in the mystery of anonymity and uncertainty, is a truly horrifying experience.

The story is told in a series of flashes of conscious remembrances interrupted by periods of unconscious hazes, with the unnamed narrator’s attempts to make sense of the nature of things based almost entirely on sensory information. He first hears the inquisitorial sentence of death then perceives the silent formation of his name on the magistrates’ thin, white lips, though we don’t learn the nature of his crime. He feels the light breeze from the sable draperies and sees seven white candles burning, which he hopes are a sign of charity and salvation. He realizes shortly, however, as they burn low, that they are another indication of his impending death. Upon this realization, he faints, but his subconscious registers men carrying him farther and farther downward, as if to a tomb; he can’t even hear his heartbeat. He awakes to full remembrance of his trial and his worst thoughts confirmed: “The blackness of eternal night encompassed me. I struggled for breath. The intensity of the darkness seemed to oppress and stifle me. The atmosphere was intolerably close. I lay still quietly, and made effort to exercise my reason.”

He cautiously sets out to survey his surroundings, but all is blackness and emptiness. He tears off a piece of his robe’s rough cloth and places it on the floor before measuring his steps away from it. He manages to get 52 paces before the moist and slippery floor, as well as his weakness, overcomes him. When he awakes, he takes 48 more paces before returning to the piece of his robe, completing what he believes are the 50 yards around the perimeter but, when he’s able to see the room later, turn out to be much fewer.

He then determines to cross the room, but he trips on his robe, falling headfirst to the ground. After a moment, he realizes that his face is not resting on the hard surface but rather is hanging over the side of a pit, deep and treacherous, filled with the stench of fungi and the miasma of stagnant water. “And the death just avoided was of that very character which I had regarded as fabulous and frivolous in the tales respecting the Inquisition. To the victims of its tyranny, there was the choice of death with its direst physical agonies, or death with its most hideous moral horrors. I had been reserved for the latter.”

Poe is a mainstay of Halloween

He retreats from the pit back to the wall and falls asleep. When he awakes, he finds himself strapped to a board, the only movement permitted that of his hand to reach out for some food left for him. And looking upward, he can see a pendulum moving back and forth, descending ever so slowly toward him with an ominous hiss. “Having failed to fall [into the pit], it was not part of the demon plan to hurl me into the abyss, and thus a different … destruction awaited me.” What’s more, “Looking to the right, I saw several enormous rats … had issued from the well, which lay just within view to my right. Even then, while I gazed, they came up in troops, hurriedly, with ravenous eyes allured by the scent of the meat [left for me].”

Suddenly, he has a thought. If he can only free himself from the surcingle strapping him down, he could escape both the rats and the ever-ponderous pendulum that threatens to slice him to bits. He reaches out and grabs the remains of the meat and “with the particles of the oily and spicy viand which now remained, I thoroughly rubbed the bandage wherever I could reach it. … Forth from the well they hurried in fresh troops. They clung to the wood – they overran it, and leaped in hundreds upon my person. The measured movement of the pendulum disturbed them not at all. Avoiding its strokes, they busied themselves with the anointed bandage. … I at length felt that I was free. … With a steady movement – cautious, sidelong, shrinking, and slow – I slid from the embrace of the bandage, and beyond the reach of the scimitar. For the moment, at least, I was free. Free! – and in the grasp of the Inquisition!”

Pick up the book or go to a dark cinema.

It turns out the narrator had never truly been free but had been watched the entire time, and now his torturers will unleash another horror upon him. The pendulum stops its descent, but the walls of his cell grow suddenly hot, smelling like the burning of iron, and in the stifling heat, the room begins to squeeze itself together. The only floor space left is in the pit, and the narrator despairs that it will get him at last. “At length for my seared and writhing body there was no longer an inch of foothold on the firm floor of the prison. I struggled no more, but the agony of my soul found vent in one loud, long, and final scream of despair. I felt that I tottered upon the brink – “

That would have been an incredible ending, but Poe felt, as far too many writers do, that he needed to add just one more thing. In this case, the French army storms the prison and rescues all the prisoners from the Inquisition. Story over. After all the horror, all the despair, a sudden happy ending? As a reader, I felt quite deflated.

And then I watched the movie and felt deflated all over again. It reminded me, with its contrived plot and use of the same horror tropes, of 1960’s “House of Usher,” adapted from a Poe story the year before. As it was made by the same team of screenwriter Matheson and director Corman, perhaps it’s no great surprise that they didn’t stray far from what had already worked for them. Stranger coming to the mansion door? Check. Vincent Price as the unhinged lord of the manor? Check. A house with a curse on it? Check. A dead or dying sister? Check. A premature burial? Check. Secret passages and haunted happenings? Check. The lord undone by the horrors/curse of the house and/or his past? Check.

In this case, Francis Barnard comes to investigate the death of his sister, Elizabeth, who was married to Nicholas Medina (Vincent Price, doing his corniest best to look beleaguered, distraught, and finally stark raving mad). Doctor Charles Leon tells Barnard that she died of shock when she saw the torture chamber concealed in the vaults of the house, but Barnard believes Nicholas was the cause, even when the lord tells him how distraught he is himself over his beloved’s death. Leon takes him into confidence and says that the chamber belonged to Nicholas’ father, Sebastian, who was the most notorious torturer of the Spanish Inquisition. As a young boy, Nicholas witnessed Sebastian torture and kill his wife and brother, who were having an affair, and that has left him damaged. Nicholas’ sister, Catherine, though, says Sebastian tortured his wife but didn’t kill her. Instead, he buried her, alive, behind a brick wall, and now Nicholas is haunted by the belief that he buried Elizabeth prematurely.

All parties go to exhume the body to be certain she was dead, descending into the castle’s crypts which look suspiciously like the crypts in “Usher,” right down to the metal doors, cobbled flooring, nametags, and rather obvious fake spiderwebs. When they open the coffin, Elizabeth’s now-dead body is clenched in a horrifying scream. The shock sends Nicholas over the edge. He begins to “hear” Elizabeth calling out to him and says he will accept any vengeance she has planned for him. Scouring the hallways and secret passages for her, he ends up in the torture chamber, which we now see includes a large stone pit. When Elizabeth makes her entrance into the chamber, “bloodied” from her experience, Nicholas falls down the stairs, completely knocked out. Leon then enters, sweeping up Elizabeth in a passionate kiss – it seems they were having an affair and her “death” was contrived to get rid of Nicholas. Nicholas wakes up, but he has gone totally mad, now thinking he is Sebastian and Elizabeth and Leon are Isabella and Bartolome, Sebastian’s wife and brother. He imprisons Elizabeth in an iron box and struggles with Leon, who falls dead into the pit. When Barnard appears, “Sebastian” somehow thinks he is now Bartolome, and he puts the young man under the swinging pendulum. Just as the blade is about to slice through him, Catherine races in with a servant to rescue him. Nicholas and the servant fight, with both falling into the pit to their deaths. Catherine orders the chamber sealed, leaving Elizabeth imprisoned for eternity.

Non-Standard Deviations

Aside from the titular objects, everything was a deviation from the original story, and you’re more likely to come away laughing at the contrivances than feeling horrified.

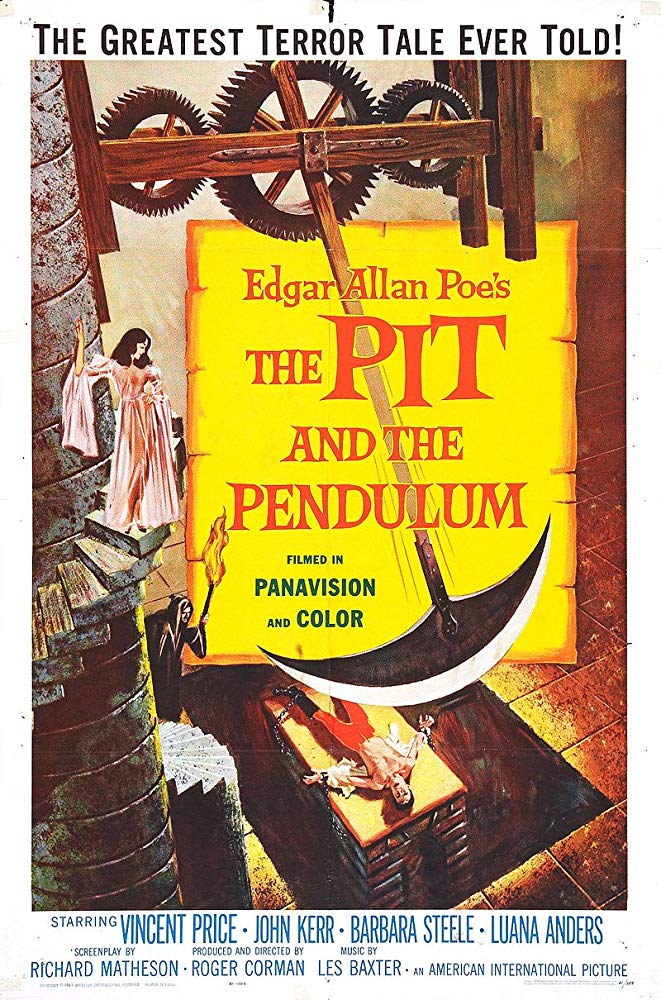

The poster for the film.

The Final Cut

So, how did “The Pit and the Pendulum” as a movie fare as a short story adaptation overall? As I said, not even close. The acting was comical, at best, wooden, at worst, and the production values were more typical of Corman’s legendary B movies than in “Usher.” I would give it a D+ on one of my more generous days.

What do you think? Do you agree? Disagree? Please add your comments in the section below.

– Miriam Ruff, Content Creator, PoetsIN

DISCLAIMER: The opinions discussed in this blog post are solely those of the blogger and do not necessarily represent any thoughts, values, or opinions of PoetsIN and any of its affiliate groups.

Please follow and like us:

Welcome a Halloween special of our series of “Have You Watched a Good Book Lately?”

The series’ intention is to track a number of books’ progression from the printed page to the silver screen and assess how well or how badly the filmmakers accomplished each of the adaptations.

One of the many Pit and the Pendulum book cover

Today we’re going to be discussing “The Pit and the Pendulum,” a short story written by Edgar Allen Poe first published in 1842 in the literary annual The Gift: A Christmas and New Year’s Present for 1843 and adapted for the screen in 1961 as “Pit and the Pendulum” by famed science fiction and horror writer Richard Matheson and “B”-film director Roger Corman (414 producer credits and 56 directorial credits). It has been adapted for film a number of other times, but for the purposes of this blog, we will be looking at the 1961 Corman version. For those of you unfamiliar with the basic premise, here is a brief synopsis of the short story (adapted from Wikipedia) and the film (taken from imdb.com):

“An unnamed prisoner of the Spanish Inquisition, convicted of an unspecified crime, explicitly describes his experience of being tortured. The story is especially effective at inspiring fear in the reader because of its heavy focus on the senses, such as sound, which imbued a sense of reality, unlike many of Poe’s other stories which are aided by the supernatural. It should be noted that, while the events are horrifying, Poe did take numerous liberties with historical facts while writing the story.”

“In the sixteenth century, Francis Barnard travels to Spain to clarify the strange circumstances of his sister’s death after she had married the son of a cruel Spanish Inquisitor.”

Our old friend Poe

From the Source’s Mouth

Let’s start our discussion with one of the main concerns of any story adaptation – how true is the film to the source material? Well, both the story and the film refer to the Spanish Inquisition (though that event occurred before the time period in which the film was set), and both do contain a pit and a pendulum somewhere along the line, but that’s about where the similarity ends. It’s a shame, as the original story, awash in the mystery of anonymity and uncertainty, is a truly horrifying experience.

The story is told in a series of flashes of conscious remembrances interrupted by periods of unconscious hazes, with the unnamed narrator’s attempts to make sense of the nature of things based almost entirely on sensory information. He first hears the inquisitorial sentence of death then perceives the silent formation of his name on the magistrates’ thin, white lips, though we don’t learn the nature of his crime. He feels the light breeze from the sable draperies and sees seven white candles burning, which he hopes are a sign of charity and salvation. He realizes shortly, however, as they burn low, that they are another indication of his impending death. Upon this realization, he faints, but his subconscious registers men carrying him farther and farther downward, as if to a tomb; he can’t even hear his heartbeat. He awakes to full remembrance of his trial and his worst thoughts confirmed: “The blackness of eternal night encompassed me. I struggled for breath. The intensity of the darkness seemed to oppress and stifle me. The atmosphere was intolerably close. I lay still quietly, and made effort to exercise my reason.”

He cautiously sets out to survey his surroundings, but all is blackness and emptiness. He tears off a piece of his robe’s rough cloth and places it on the floor before measuring his steps away from it. He manages to get 52 paces before the moist and slippery floor, as well as his weakness, overcomes him. When he awakes, he takes 48 more paces before returning to the piece of his robe, completing what he believes are the 50 yards around the perimeter but, when he’s able to see the room later, turn out to be much fewer.

He then determines to cross the room, but he trips on his robe, falling headfirst to the ground. After a moment, he realizes that his face is not resting on the hard surface but rather is hanging over the side of a pit, deep and treacherous, filled with the stench of fungi and the miasma of stagnant water. “And the death just avoided was of that very character which I had regarded as fabulous and frivolous in the tales respecting the Inquisition. To the victims of its tyranny, there was the choice of death with its direst physical agonies, or death with its most hideous moral horrors. I had been reserved for the latter.”

Poe is a mainstay of Halloween

He retreats from the pit back to the wall and falls asleep. When he awakes, he finds himself strapped to a board, the only movement permitted that of his hand to reach out for some food left for him. And looking upward, he can see a pendulum moving back and forth, descending ever so slowly toward him with an ominous hiss. “Having failed to fall [into the pit], it was not part of the demon plan to hurl me into the abyss, and thus a different … destruction awaited me.” What’s more, “Looking to the right, I saw several enormous rats … had issued from the well, which lay just within view to my right. Even then, while I gazed, they came up in troops, hurriedly, with ravenous eyes allured by the scent of the meat [left for me].”

Suddenly, he has a thought. If he can only free himself from the surcingle strapping him down, he could escape both the rats and the ever-ponderous pendulum that threatens to slice him to bits. He reaches out and grabs the remains of the meat and “with the particles of the oily and spicy viand which now remained, I thoroughly rubbed the bandage wherever I could reach it. … Forth from the well they hurried in fresh troops. They clung to the wood – they overran it, and leaped in hundreds upon my person. The measured movement of the pendulum disturbed them not at all. Avoiding its strokes, they busied themselves with the anointed bandage. … I at length felt that I was free. … With a steady movement – cautious, sidelong, shrinking, and slow – I slid from the embrace of the bandage, and beyond the reach of the scimitar. For the moment, at least, I was free. Free! – and in the grasp of the Inquisition!”

Pick up the book or go to a dark cinema.

It turns out the narrator had never truly been free but had been watched the entire time, and now his torturers will unleash another horror upon him. The pendulum stops its descent, but the walls of his cell grow suddenly hot, smelling like the burning of iron, and in the stifling heat, the room begins to squeeze itself together. The only floor space left is in the pit, and the narrator despairs that it will get him at last. “At length for my seared and writhing body there was no longer an inch of foothold on the firm floor of the prison. I struggled no more, but the agony of my soul found vent in one loud, long, and final scream of despair. I felt that I tottered upon the brink – “

That would have been an incredible ending, but Poe felt, as far too many writers do, that he needed to add just one more thing. In this case, the French army storms the prison and rescues all the prisoners from the Inquisition. Story over. After all the horror, all the despair, a sudden happy ending? As a reader, I felt quite deflated.

And then I watched the movie and felt deflated all over again. It reminded me, with its contrived plot and use of the same horror tropes, of 1960’s “House of Usher,” adapted from a Poe story the year before. As it was made by the same team of screenwriter Matheson and director Corman, perhaps it’s no great surprise that they didn’t stray far from what had already worked for them. Stranger coming to the mansion door? Check. Vincent Price as the unhinged lord of the manor? Check. A house with a curse on it? Check. A dead or dying sister? Check. A premature burial? Check. Secret passages and haunted happenings? Check. The lord undone by the horrors/curse of the house and/or his past? Check.

In this case, Francis Barnard comes to investigate the death of his sister, Elizabeth, who was married to Nicholas Medina (Vincent Price, doing his corniest best to look beleaguered, distraught, and finally stark raving mad). Doctor Charles Leon tells Barnard that she died of shock when she saw the torture chamber concealed in the vaults of the house, but Barnard believes Nicholas was the cause, even when the lord tells him how distraught he is himself over his beloved’s death. Leon takes him into confidence and says that the chamber belonged to Nicholas’ father, Sebastian, who was the most notorious torturer of the Spanish Inquisition. As a young boy, Nicholas witnessed Sebastian torture and kill his wife and brother, who were having an affair, and that has left him damaged. Nicholas’ sister, Catherine, though, says Sebastian tortured his wife but didn’t kill her. Instead, he buried her, alive, behind a brick wall, and now Nicholas is haunted by the belief that he buried Elizabeth prematurely.

All parties go to exhume the body to be certain she was dead, descending into the castle’s crypts which look suspiciously like the crypts in “Usher,” right down to the metal doors, cobbled flooring, nametags, and rather obvious fake spiderwebs. When they open the coffin, Elizabeth’s now-dead body is clenched in a horrifying scream. The shock sends Nicholas over the edge. He begins to “hear” Elizabeth calling out to him and says he will accept any vengeance she has planned for him. Scouring the hallways and secret passages for her, he ends up in the torture chamber, which we now see includes a large stone pit. When Elizabeth makes her entrance into the chamber, “bloodied” from her experience, Nicholas falls down the stairs, completely knocked out. Leon then enters, sweeping up Elizabeth in a passionate kiss – it seems they were having an affair and her “death” was contrived to get rid of Nicholas. Nicholas wakes up, but he has gone totally mad, now thinking he is Sebastian and Elizabeth and Leon are Isabella and Bartolome, Sebastian’s wife and brother. He imprisons Elizabeth in an iron box and struggles with Leon, who falls dead into the pit. When Barnard appears, “Sebastian” somehow thinks he is now Bartolome, and he puts the young man under the swinging pendulum. Just as the blade is about to slice through him, Catherine races in with a servant to rescue him. Nicholas and the servant fight, with both falling into the pit to their deaths. Catherine orders the chamber sealed, leaving Elizabeth imprisoned for eternity.

Non-Standard Deviations

Aside from the titular objects, everything was a deviation from the original story, and you’re more likely to come away laughing at the contrivances than feeling horrified.

The poster for the film.

The Final Cut

So, how did “The Pit and the Pendulum” as a movie fare as a short story adaptation overall? As I said, not even close. The acting was comical, at best, wooden, at worst, and the production values were more typical of Corman’s legendary B movies than in “Usher.” I would give it a D+ on one of my more generous days.

What do you think? Do you agree? Disagree? Please add your comments in the section below.

– Miriam Ruff, Content Creator, PoetsIN

DISCLAIMER: The opinions discussed in this blog post are solely those of the blogger and do not necessarily represent any thoughts, values, or opinions of PoetsIN and any of its affiliate groups.

admin