We have a very special blog piece for you this week. This piece comes from an amazing art teacher in a female prison, Ella Whittlestone.

In spending the last year teaching art on the female education wing of a prison, I was granted a unique and privileged insight into the role education plays within the context of rehabilitation. Being immersed in this locked away community of people has taught me a lot about humanity, primarily that stereotypes serve very little purpose and are better off ignored – the diverse range of individuals I have crossed paths with during my time inside has reinforced my belief that ‘criminal’, ’prisoner’, or ’offender’ tells you very little about the person upon which this label is stuck. I have even on occasion felt compelled to challenge those who self-stigmatize with comments such as ‘What do you expect? I’m a criminal’, by responding that surely first and foremost and above all else, they are a person.

Stereotypes and stigma aside, teaching in a prison has allowed me to observe how different people present themselves to the world, whilst seeking out patterns and potential correlations. I have structured my response to the question of ‘What do prisoners and ex-offenders need to learn?’ around what I consider to be four key themes:

Acceptance, self-worth, conquering fear and connection.

Acceptance

Being a person is hard. This is something that does not get acknowledged as much as it perhaps should. Throughout our lives we are faced with a near constant myriad of expectation, pressure and change outside of our control, all of which shape our sense of self and ability to create a meaningful existence.

As a general rule, resisting or fighting against something tends to lead only to further tension. A certain relief comes from the simple act of accepting things exactly as they are. In this chaotic world there is so much going on that is out of our hands, but the one things we can always change (or at least become more aware of) is how we respond to what is going on. Simply acknowledging when something has made you feel upset, angry, anxious etc. can be very helpful in both detaching from, and consequently dealing with, this feeling; the feeling is not you. It may sound simplistic, but understanding the difference between, for example, ‘I am frustrated’ and ‘I feel frustrated’ can help in letting go of something that need not define you.

One of the female prison residents I worked with in the art class once wrote:

‘Respect is a first requirement towards oneself, and respect towards the other is a logical consequence of the first’.

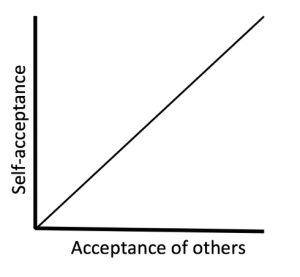

I believe this applies similarly to acceptance, in that we are more likely to accept others if we first accept ourselves. Those who find fault in others are more than likely reflecting their own feelings of being at fault in some fundamental way, and in doing so attempting to lift or alleviate this pain. After all, why would you need to find fault in others if you were totally and completely content in yourself? Perhaps this general trend could be framed as simply as in the graph below:

It is an experience we are probably all familiar with – someone else trying to bring you down in an attempt to raise themselves up. This can lead to a vicious circle, with both parties feeling worse about themselves, prompting yet more fault-finding and put-downs in further attempts to combat insecurity. Something has to break the cycle. I would suggest that in order to fully accept what is external to us (the situation we find ourselves in, the actions of those around us), we must first attempt to accept the messy internal world of ourselves.

Self-Worth

I would argue that low self-worth is a significant contributing factor when it comes to crime. If you consider yourself to have little or no worth, this will be reflected in the choices you make – choices which as a result are more likely to cause harm.

Think about this within the context of monetary worth. Imagine you own two watches; one cost a fiver from a dodgy market stall, whilst the other is designer, priced at several hundred pounds. How does the way you treat these two watches differ? Which are you more likely to damage or lose?

As a general rule, the more you have invested in something, the better you will take care of it. Those who have not developed a strong sense of self-worth, often find themselves taking on the metaphorical role of the cheap market stall watch.

Though everyone ought to feel valued and worthy of existence, this is not something that comes easily. To complicate things further, in trying to feel okay about ourselves we will often look to others for reassurance. This is a problem because other people are insecure in their own unique ways, and likely to be immersed in a simultaneous struggle with their own sense of self-worth. Therefore, other people are generally not a reliable source of the validation we crave, often serving instead to further our sense of fault or unworthiness, through criticism or unkind behaviour.

The unfortunate truth would appear to be, that the less value you place on yourself, the less care you take when it comes to your wellbeing. I take the view that destructive behaviours and habits, such as abuse and addiction, arise from an emptiness where acceptance and self-worth ought to be. In attempts to fill this painful void, those that consider themselves to be cheap market stall watches seek to distract, impair or punish themselves in a number of ways, feeling on some level that they are worthy of no better. Self-harm in various forms, whether it be over-eating or injecting heroin into your eyeballs, serves to give yourself the message ‘I am not worth looking after’. Even if there is a temporary sense of pleasure or release that accompanies such things, the reality and aftermath is rarely positive.

Seeking help, taking steps towards recovery, choosing rehabilitation, all require the belief that you are a worn out or broken watch that is worthy of repair.

I therefore believe that one of the most important things for offenders and all people to learn is this: you have intrinsic value just as you are. This does not mean you cannot grow and improve yourself, but that in order to do so you must start from a place of self-acceptance, knowing that despite your imperfections and insecurities you are not intrinsically bad, nor wrong, nor unworthy of existence. Easier said than done, but perhaps deciding to unconditionally accept and value yourself as though an expensive designer watch is a leap of faith worth taking.

Conquering Fear

Defence mechanisms seem to be a common trait of people who have been hurt or abused in some way. As a form of self-preservation, defences arise from a need to protect oneself from criticism, hostility, aggression; interesting then, that it is precisely these characteristics that are commonly expressed by those with such defence mechanisms.

Despite the seeming contradiction of this, those who shout the loudest are often the least confident in themselves; it takes a solid sense of self-worth to show vulnerability, to be confident enough to say that you really are not confident at all.

I once brought this up in class discussion, and one of the ladies referenced the analogy of a turtle’s tough shell, designed to protect it’s soft and vulnerable insides. The sad thing is, defences intended to protect oneself from harm will often end up pushing people away, sacrificing the potential for positive connection out of fear that it could lead to further hurt, trauma or betrayal; like putting up a window to the weather, you may not suffer the storms so badly, but you also won’t feel the full warmth of the sun.

Some would seem to have taken this to the extreme, moulding themselves into someone that others fear. This perhaps arises from a sense that becoming a source of fear will serve as protection, and allow for some autonomy. This is arguably just as relevant within the context of self-harm, which is particularly prevalent among prison residents. For those who have such low self-worth that they feel compelled to physically hurt themselves, at least it is something over which they have control.

I have come to recognise the frequently stated ‘I can’t draw’ a form of defence mechanism. Many people would seemingly rather control and apply self-criticisms or negative labels than leave themselves open to receiving this from others.

So what is the underlying cause of these defence mechanisms? I would argue fear; we defend ourselves when we are under threat and afraid.

One surprisingly common fear that I often come across in prison, is the fear of being wrong. The safety that comes with colouring inside the lines and thinking inside the box is predominantly favoured, as though drawing a line out of place would confirm a fear of being wrong in and of oneself. The art course I run has revolved largely around portraiture. Many of the women are hesitant to look in the mirror when it comes to drawing a self-portrait. They do not like what they see, and perhaps on some level even fear themselves.

By the way that I structure and deliver the course, I have sought to question and dismantle some of these fears, most notably the fear of difference. This seems to me to be a somewhat primitive fear that is likely to have once served us in terms of survival; trusting only what you know may well have saved you from many threats or predators back when we were hunter-gatherers. However, having now moved past the times of sticking to our tribe and distrust of ‘imposters’, fearing difference arguably no longer serves us so well. Whilst you can see why concerned parents drill into their children that they must ‘never trust strangers’, I can’t help but wonder if this mind-set is promoting unnecessarily high defences and distrust of others later on in life. Could it not be argued that instances of prejudice and discrimination arise from a deep-rooted fear of what is different?

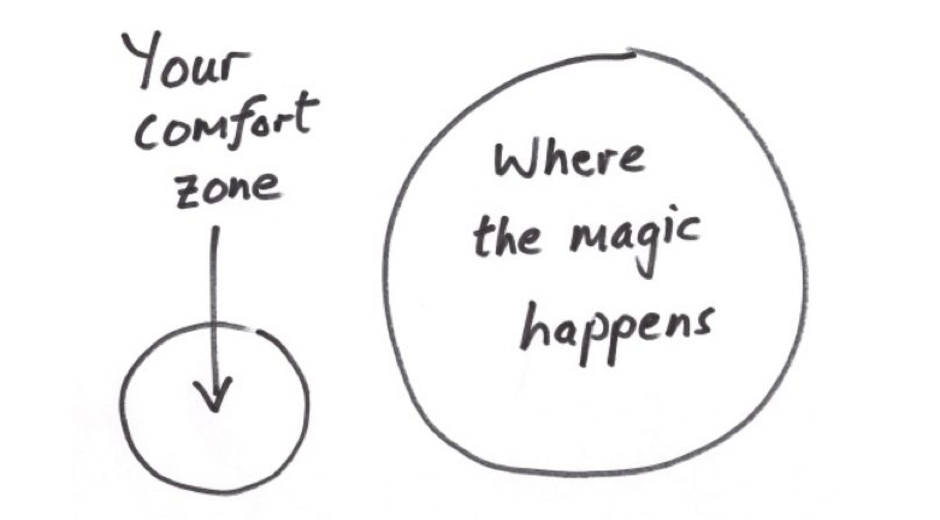

In a similar vein, fear of the unknown is seemingly the fuel of inhibition when it comes to comfort zone expansion. We will often choose what is familiar over what is good for us, which would explain why so many people stay with abusive partners, or jobs that make them miserable, or return to lives of crime after release from prison. People often claim to regret not doing things or making changes, and it seems that fear is what gets in the way.

https://rachelbritton.com/3-incorrect-assumptions-about-leaving-your-comfort-zone/

Learning to trust in the unknown, to ‘feel the fear and do it anyway’ takes a great deal of courage, and is not something we can necessarily do on our own.

Connection

No one wants to be a puzzle piece that doesn’t fit; I strongly believe that on some level we all want to belong and to be a part of something bigger than ourselves. Connecting with others and the environment around us gives life meaning in a way that arguably no substance can offer.

It is for this reason that I have taken the opportunity to initiate a collaborative community drawing project titled, ‘Connect Draw’. I have invited school children, artists, university students, art teachers and trainees as well as prison residents and staff to offer their unique response to the same set of simple drawing instructions; those otherwise divided by labels and stereotypes are united in a shared artistic purpose, through the universally human act of drawing. The drawing outcomes will eventually be exhibited alongside one another, granted equal worth and status within a shared space. The project is intended to stand as a model of how an ideal society might be, at a time when there seems to be a greater emphasis on what divides as opposed to connects us.

Having offered my response to the question of ‘What do prisoners and ex-offenders need to learn?’, I would like to now say that I consider the themes discussed to be of universal relevance; acceptance of yourself and others in order to overcome fear and form meaningful connections is surely a lesson to be learnt by all of humanity, regardless of which side of the bars you happen to be on.

Our biggest thanks to Ella for this wonderfully thoughtful piece. What do you think prisoners need to learn?

Please follow and like us:

We have a very special blog piece for you this week. This piece comes from an amazing art teacher in a female prison, Ella Whittlestone.

In spending the last year teaching art on the female education wing of a prison, I was granted a unique and privileged insight into the role education plays within the context of rehabilitation. Being immersed in this locked away community of people has taught me a lot about humanity, primarily that stereotypes serve very little purpose and are better off ignored – the diverse range of individuals I have crossed paths with during my time inside has reinforced my belief that ‘criminal’, ’prisoner’, or ’offender’ tells you very little about the person upon which this label is stuck. I have even on occasion felt compelled to challenge those who self-stigmatize with comments such as ‘What do you expect? I’m a criminal’, by responding that surely first and foremost and above all else, they are a person.

Stereotypes and stigma aside, teaching in a prison has allowed me to observe how different people present themselves to the world, whilst seeking out patterns and potential correlations. I have structured my response to the question of ‘What do prisoners and ex-offenders need to learn?’ around what I consider to be four key themes:

Acceptance, self-worth, conquering fear and connection.

Acceptance

Being a person is hard. This is something that does not get acknowledged as much as it perhaps should. Throughout our lives we are faced with a near constant myriad of expectation, pressure and change outside of our control, all of which shape our sense of self and ability to create a meaningful existence.

As a general rule, resisting or fighting against something tends to lead only to further tension. A certain relief comes from the simple act of accepting things exactly as they are. In this chaotic world there is so much going on that is out of our hands, but the one things we can always change (or at least become more aware of) is how we respond to what is going on. Simply acknowledging when something has made you feel upset, angry, anxious etc. can be very helpful in both detaching from, and consequently dealing with, this feeling; the feeling is not you. It may sound simplistic, but understanding the difference between, for example, ‘I am frustrated’ and ‘I feel frustrated’ can help in letting go of something that need not define you.

One of the female prison residents I worked with in the art class once wrote:

I believe this applies similarly to acceptance, in that we are more likely to accept others if we first accept ourselves. Those who find fault in others are more than likely reflecting their own feelings of being at fault in some fundamental way, and in doing so attempting to lift or alleviate this pain. After all, why would you need to find fault in others if you were totally and completely content in yourself? Perhaps this general trend could be framed as simply as in the graph below:

It is an experience we are probably all familiar with – someone else trying to bring you down in an attempt to raise themselves up. This can lead to a vicious circle, with both parties feeling worse about themselves, prompting yet more fault-finding and put-downs in further attempts to combat insecurity. Something has to break the cycle. I would suggest that in order to fully accept what is external to us (the situation we find ourselves in, the actions of those around us), we must first attempt to accept the messy internal world of ourselves.

Self-Worth

I would argue that low self-worth is a significant contributing factor when it comes to crime. If you consider yourself to have little or no worth, this will be reflected in the choices you make – choices which as a result are more likely to cause harm.

Think about this within the context of monetary worth. Imagine you own two watches; one cost a fiver from a dodgy market stall, whilst the other is designer, priced at several hundred pounds. How does the way you treat these two watches differ? Which are you more likely to damage or lose?

As a general rule, the more you have invested in something, the better you will take care of it. Those who have not developed a strong sense of self-worth, often find themselves taking on the metaphorical role of the cheap market stall watch.

Though everyone ought to feel valued and worthy of existence, this is not something that comes easily. To complicate things further, in trying to feel okay about ourselves we will often look to others for reassurance. This is a problem because other people are insecure in their own unique ways, and likely to be immersed in a simultaneous struggle with their own sense of self-worth. Therefore, other people are generally not a reliable source of the validation we crave, often serving instead to further our sense of fault or unworthiness, through criticism or unkind behaviour.

The unfortunate truth would appear to be, that the less value you place on yourself, the less care you take when it comes to your wellbeing. I take the view that destructive behaviours and habits, such as abuse and addiction, arise from an emptiness where acceptance and self-worth ought to be. In attempts to fill this painful void, those that consider themselves to be cheap market stall watches seek to distract, impair or punish themselves in a number of ways, feeling on some level that they are worthy of no better. Self-harm in various forms, whether it be over-eating or injecting heroin into your eyeballs, serves to give yourself the message ‘I am not worth looking after’. Even if there is a temporary sense of pleasure or release that accompanies such things, the reality and aftermath is rarely positive.

Seeking help, taking steps towards recovery, choosing rehabilitation, all require the belief that you are a worn out or broken watch that is worthy of repair.

I therefore believe that one of the most important things for offenders and all people to learn is this: you have intrinsic value just as you are. This does not mean you cannot grow and improve yourself, but that in order to do so you must start from a place of self-acceptance, knowing that despite your imperfections and insecurities you are not intrinsically bad, nor wrong, nor unworthy of existence. Easier said than done, but perhaps deciding to unconditionally accept and value yourself as though an expensive designer watch is a leap of faith worth taking.

Conquering Fear

Defence mechanisms seem to be a common trait of people who have been hurt or abused in some way. As a form of self-preservation, defences arise from a need to protect oneself from criticism, hostility, aggression; interesting then, that it is precisely these characteristics that are commonly expressed by those with such defence mechanisms.

Despite the seeming contradiction of this, those who shout the loudest are often the least confident in themselves; it takes a solid sense of self-worth to show vulnerability, to be confident enough to say that you really are not confident at all.

I once brought this up in class discussion, and one of the ladies referenced the analogy of a turtle’s tough shell, designed to protect it’s soft and vulnerable insides. The sad thing is, defences intended to protect oneself from harm will often end up pushing people away, sacrificing the potential for positive connection out of fear that it could lead to further hurt, trauma or betrayal; like putting up a window to the weather, you may not suffer the storms so badly, but you also won’t feel the full warmth of the sun.

Some would seem to have taken this to the extreme, moulding themselves into someone that others fear. This perhaps arises from a sense that becoming a source of fear will serve as protection, and allow for some autonomy. This is arguably just as relevant within the context of self-harm, which is particularly prevalent among prison residents. For those who have such low self-worth that they feel compelled to physically hurt themselves, at least it is something over which they have control.

I have come to recognise the frequently stated ‘I can’t draw’ a form of defence mechanism. Many people would seemingly rather control and apply self-criticisms or negative labels than leave themselves open to receiving this from others.

So what is the underlying cause of these defence mechanisms? I would argue fear; we defend ourselves when we are under threat and afraid.

One surprisingly common fear that I often come across in prison, is the fear of being wrong. The safety that comes with colouring inside the lines and thinking inside the box is predominantly favoured, as though drawing a line out of place would confirm a fear of being wrong in and of oneself. The art course I run has revolved largely around portraiture. Many of the women are hesitant to look in the mirror when it comes to drawing a self-portrait. They do not like what they see, and perhaps on some level even fear themselves.

By the way that I structure and deliver the course, I have sought to question and dismantle some of these fears, most notably the fear of difference. This seems to me to be a somewhat primitive fear that is likely to have once served us in terms of survival; trusting only what you know may well have saved you from many threats or predators back when we were hunter-gatherers. However, having now moved past the times of sticking to our tribe and distrust of ‘imposters’, fearing difference arguably no longer serves us so well. Whilst you can see why concerned parents drill into their children that they must ‘never trust strangers’, I can’t help but wonder if this mind-set is promoting unnecessarily high defences and distrust of others later on in life. Could it not be argued that instances of prejudice and discrimination arise from a deep-rooted fear of what is different?

In a similar vein, fear of the unknown is seemingly the fuel of inhibition when it comes to comfort zone expansion. We will often choose what is familiar over what is good for us, which would explain why so many people stay with abusive partners, or jobs that make them miserable, or return to lives of crime after release from prison. People often claim to regret not doing things or making changes, and it seems that fear is what gets in the way.

https://rachelbritton.com/3-incorrect-assumptions-about-leaving-your-comfort-zone/

Learning to trust in the unknown, to ‘feel the fear and do it anyway’ takes a great deal of courage, and is not something we can necessarily do on our own.

Connection

No one wants to be a puzzle piece that doesn’t fit; I strongly believe that on some level we all want to belong and to be a part of something bigger than ourselves. Connecting with others and the environment around us gives life meaning in a way that arguably no substance can offer.

It is for this reason that I have taken the opportunity to initiate a collaborative community drawing project titled, ‘Connect Draw’. I have invited school children, artists, university students, art teachers and trainees as well as prison residents and staff to offer their unique response to the same set of simple drawing instructions; those otherwise divided by labels and stereotypes are united in a shared artistic purpose, through the universally human act of drawing. The drawing outcomes will eventually be exhibited alongside one another, granted equal worth and status within a shared space. The project is intended to stand as a model of how an ideal society might be, at a time when there seems to be a greater emphasis on what divides as opposed to connects us.

Having offered my response to the question of ‘What do prisoners and ex-offenders need to learn?’, I would like to now say that I consider the themes discussed to be of universal relevance; acceptance of yourself and others in order to overcome fear and form meaningful connections is surely a lesson to be learnt by all of humanity, regardless of which side of the bars you happen to be on.

Our biggest thanks to Ella for this wonderfully thoughtful piece. What do you think prisoners need to learn?

admin