Welcome back to our blog series “Have You Watched a Good Book Lately?”

The series’ intention is to track a number of books’ progression from the printed page to the silver screen and assess how well or how badly the filmmakers accomplished each of the adaptations.

Today we’re going to be discussing “Don’t Look Now,” a short story written by Daphne du Maurier, first published in the collection Not After Midnight in 1971 and adapted for the screen in 1973 by screenwriter Alan Scott and cinematographer-turned-director Nicholas Roeg (“The Man Who Fell to Earth,” “Walkabout”). For those of you unfamiliar with the basic premise, here is a brief synopsis adapted from imdb.com:

Don’t Look Now book cover

“A married couple grieving the recent death of their young daughter is staying in Venice, where they encounter two elderly sisters, one of whom is blind but psychic and brings a warning from beyond the grave they thought they left behind.”

From the Source’s Mouth

Let’s start our discussion with one of the main concerns of any story adaptation – how true is the film to the source material? Diane Setterfield, author of “The Thirteenth Tale,” said, “There is something about words. In expert hands, manipulated deftly, they take you prisoner. Wind themselves around your limbs like spider silk, and when you are so enthralled you cannot move, they pierce your skin, enter your blood, numb your thoughts. Inside you they work their magic.” Daphne du Maurier, best known for such thrilling works as “Rebecca,” “Jamaica Inn,” and “The House on the Strand,” was an expert writer, and she wove her tale deftly.

The author herself, Daphne du Maurier

This story takes place in Venice, Italy, where John and Laura Baxter are on holiday, trying to cope with the grief of losing their young daughter, Christine, to meningitis. John’s goal is to spend a couple of weeks sightseeing famous landmarks so that Laura, who is very emotionally fragile, can regain her equilibrium. Laura meets up with twin sisters, one of whom is blind but also psychic, and from them she gets the solace she needs. The psychic tells her she’s “seen” her dead daughter sitting between her and her husband, happy and laughing – it transforms Laura into the happy woman she was before Christine’s death, but it also leads to a wildly escalating series of events of future sight, miscommunication, danger, and a deadly case of mistaken identity.

It definitely helped that du Maurier clearly knew Venice, and she took great care to describe not only the look of the buildings and the extensive network of canals, but also how the water reflects the sunlight and sloshes against the buildings, how the houses “close in” on the couple when they walk at night, and how the canals, so alive with people and traffic during the day, become dank and full of stifling shadows in the darkness. The setting and the feelings it generated were the genuine articles.

Film, though, is a visual medium, and Roeg knew that he had to weave the story and its ever-increasing levels of suspense and terror with his camera and lighting. He chose to start the movie not with John (played by Donald Sutherland) and Laura (played by Julie Christie) in Venice but in their serene home in the English countryside with their two children, Johnnie and Christine. Here, John is an architect who will be restoring a cathedral in Venice. He’s going through some slides of the structure while the children play outside. Christine runs happily by the stream wearing a red plastic mac. We watch her upside-down reflection in the water as she trots along the bank. In short order, though, John spies a strange, red-coated figure in one of the slides, spills his wine in surprise, and as the liquid oozes through the image like blood, he looks out the window with sudden, surprising panic. Running outside, he finds Christine drowned in the stream, his grief-stricken cries terrible over her lifeless body. While absent from the story, this scene is incredibly important visually, as it foreshadows some of John’s character as well as images that will appear later in the film.

John is an architect who will be restoring a cathedral in Venice.

Months go by and the couple heads to Venice so John can work on the cathedral. In the same way du Maurier used words to paint the city in its many hues, Roeg used his camera and the ambient lighting to illuminate the vivaciousness of the city and its charm by day; the closed-in buildings and frightening depths of the canals at night; and the surreal appearance of a psychic vision playing out its final moments at the end.

While in a restaurant, Laura runs into the two sisters of the story when she directs them to the restroom. Though in the telling Christine’s outfit has changed from the blue-and-white dress of the story to the red mac of the film (an important change), the blind sister again tells Laura that her little girl is sitting between her and her husband and that she is happy. When Laura enthusiastically delivers the news to John at the table, she faints with the emotion, dragging down the tablecloth with her and smashing the dishes and glassware in the process. While this may seem like an unnecessary complication to the story, Laura lying amongst the broken pieces is another bit of visual foreshadowing that Roeg adds to increase the viewers’ sense of tension.

Laura runs into the sisters again, and they warn her of impending danger, saying that the couple must leave Venice. When she tells John, however, he is outraged by the “nonsense” and refuses to give in to her pleading. The two, though, are woken in the middle of the night by a phone call from Johnnie’s school in England informing them that their son has had an accident (in the story, he has appendicitis). Laura, seeing this as the reason for the sisters’ warning, immediately makes plans to be on the next flight out of Venice to be with him, and John sees her off first thing in the morning before he returns to work at the cathedral.

John, though, has a strange experience. Traveling away from the city several hours later, he sees a small boat passing them, heading back towards it. On it are Christine, dressed in black, and the two sisters, one on either side. They don’t appear to hear him calling them, so he races back to the hotel where he assumes Laura will try to find him. The manager, though, closing the hotel for the winter season, says no one else is there, and, no, Laura has not come back. Roeg, framing John in the middle of an empty hotel lobby, its furniture already draped with sheets and dust motes floating in the air, paints a bleak picture of confusion and isolation. John goes to the police, but they are reluctant to help him with his wild stories of the two sisters’ psychic abilities and the possibility they forced Laura to come back for some devious purpose. They have a murderer on the loose, and they have more important things to do than indulge his fantasies. They do agree, though, to look into the sisters’ identities.

In the meantime, John calls his son’s school to get an update, and they – quite surprisingly – put him through to his wife, who has been there the whole time. Completely confused, John goes to the police station, where the blind sister is being held, has her released, and profusely apologizes to her for the entire mess he’s created. As he gets her back to her hotel and to her sister, though, she heads into a psychic trance; unnerved, he flees before he can hear her warning him of the danger up ahead.

As John runs through the darkened canal banks, Roeg spins the film full circle, returning to Christine and her red mac of warning. John hears a girl’s terrified cry and sees a small figure also dressed in a red mac with a hood running down the alleyway while being chased by an angry man. Roeg juxtaposes the inverted image of Christine running by the stream with the right-side-up image of this girl running by the canals’ dark waters. We feel John’s desperate desire to protect this child, as he couldn’t protect his own daughter from her fate. He continues to follow her until she finally runs into a crumbling building. “You’re safe,” he tells her, reaching out his hand. “I won’t hurt you.” But when she turns around, we see the lie. She is an old dwarf, not a child, and as she pulls the long, wicked knife out of her coat, she shakes her head at his gullibility, as she probably did for all her other victims. John realizes that when he saw Laura and the sisters in the boat, what he saw was the future, the future in which they were all coming back to Venice for his funeral. “What a bloody silly way to die …” was how du Maurier phrased his final thought.

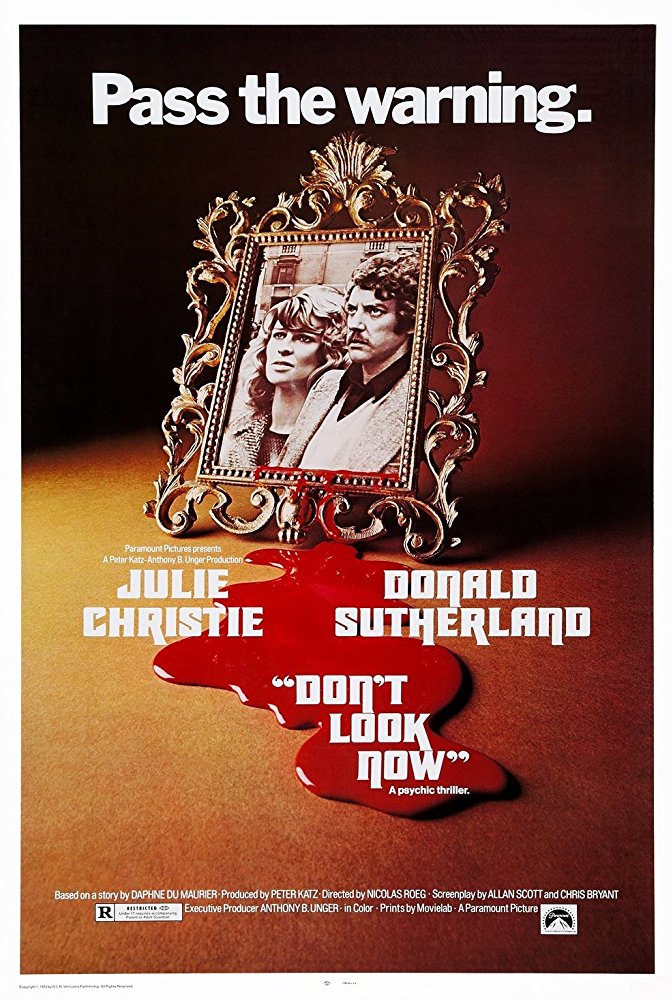

Don’t Look Now 1973 film poster.

Non-Standard Deviations

As close as the story and the film are in many ways, there are some curious differences between the two. The first is the title. “Don’t Look Now,” according to the story, was a game John and Laura played while on holidays. They would sit at a restaurant table or stand by an attraction and glance furtively at someone near them, making up wildly fantastic stories about them, what devious plots they were hatching, and how they would be found out. This was how Laura first met the twins. She and John spied them in the restaurant, and when they went into the bathroom, Laura followed to find out more and to bring back some “juicy gossip.” The title is also relevant for the dwarf at the story’s end – John had some fantastic image of who this “child” must be and what trouble she was in and ended up paying for the misconception with his life. Why Roeg chose not to incorporate any of this is rather puzzling.

Equally puzzling is a third element of foreshadowing that du Maurier uses in the story but Roeg eliminated from the film. In the story, as Laura and John walk through the city’s deserted canal banks and alleyways at night, John hears the sound of screaming and catches a glimpse of a small girl wearing a short skirt and a pixie hood running away from someone, terrified. She disappears before John can follow her, but the image unsettles him and casts a dark pall over the crumbling buildings lining the dank waterways. This scene ties directly in to the ending of both the story and the film, so one would think it should have been a vital sequence of the latter, but it wasn’t.

Which is it to be, cinema or book.

The Final Cut

So, how did “Don’t Look Now” as a movie fare as a story adaptation overall? Roeg is a visionary director, and his artistic use of camerawork, lighting, and location did justice to the original story, even if it wasn’t an exact duplicate. The missing elements, though, do detract from the finished film somewhat, so I would give it an A-; a little more, and it would have been perfect.

What do you think? Do you agree? Disagree? Please add your comments in the section below.

– Miriam Ruff, Content Creator, PoetsIN

DISCLAIMER: The opinions discussed in this blog post are solely those of the blogger and do not necessarily represent any thoughts, values, or opinions of PoetsIN and any of its affiliate groups.

Please follow and like us:

Welcome back to our blog series “Have You Watched a Good Book Lately?”

The series’ intention is to track a number of books’ progression from the printed page to the silver screen and assess how well or how badly the filmmakers accomplished each of the adaptations.

Today we’re going to be discussing “Don’t Look Now,” a short story written by Daphne du Maurier, first published in the collection Not After Midnight in 1971 and adapted for the screen in 1973 by screenwriter Alan Scott and cinematographer-turned-director Nicholas Roeg (“The Man Who Fell to Earth,” “Walkabout”). For those of you unfamiliar with the basic premise, here is a brief synopsis adapted from imdb.com:

Don’t Look Now book cover

“A married couple grieving the recent death of their young daughter is staying in Venice, where they encounter two elderly sisters, one of whom is blind but psychic and brings a warning from beyond the grave they thought they left behind.”

From the Source’s Mouth

Let’s start our discussion with one of the main concerns of any story adaptation – how true is the film to the source material? Diane Setterfield, author of “The Thirteenth Tale,” said, “There is something about words. In expert hands, manipulated deftly, they take you prisoner. Wind themselves around your limbs like spider silk, and when you are so enthralled you cannot move, they pierce your skin, enter your blood, numb your thoughts. Inside you they work their magic.” Daphne du Maurier, best known for such thrilling works as “Rebecca,” “Jamaica Inn,” and “The House on the Strand,” was an expert writer, and she wove her tale deftly.

The author herself, Daphne du Maurier

This story takes place in Venice, Italy, where John and Laura Baxter are on holiday, trying to cope with the grief of losing their young daughter, Christine, to meningitis. John’s goal is to spend a couple of weeks sightseeing famous landmarks so that Laura, who is very emotionally fragile, can regain her equilibrium. Laura meets up with twin sisters, one of whom is blind but also psychic, and from them she gets the solace she needs. The psychic tells her she’s “seen” her dead daughter sitting between her and her husband, happy and laughing – it transforms Laura into the happy woman she was before Christine’s death, but it also leads to a wildly escalating series of events of future sight, miscommunication, danger, and a deadly case of mistaken identity.

It definitely helped that du Maurier clearly knew Venice, and she took great care to describe not only the look of the buildings and the extensive network of canals, but also how the water reflects the sunlight and sloshes against the buildings, how the houses “close in” on the couple when they walk at night, and how the canals, so alive with people and traffic during the day, become dank and full of stifling shadows in the darkness. The setting and the feelings it generated were the genuine articles.

Film, though, is a visual medium, and Roeg knew that he had to weave the story and its ever-increasing levels of suspense and terror with his camera and lighting. He chose to start the movie not with John (played by Donald Sutherland) and Laura (played by Julie Christie) in Venice but in their serene home in the English countryside with their two children, Johnnie and Christine. Here, John is an architect who will be restoring a cathedral in Venice. He’s going through some slides of the structure while the children play outside. Christine runs happily by the stream wearing a red plastic mac. We watch her upside-down reflection in the water as she trots along the bank. In short order, though, John spies a strange, red-coated figure in one of the slides, spills his wine in surprise, and as the liquid oozes through the image like blood, he looks out the window with sudden, surprising panic. Running outside, he finds Christine drowned in the stream, his grief-stricken cries terrible over her lifeless body. While absent from the story, this scene is incredibly important visually, as it foreshadows some of John’s character as well as images that will appear later in the film.

John is an architect who will be restoring a cathedral in Venice.

Months go by and the couple heads to Venice so John can work on the cathedral. In the same way du Maurier used words to paint the city in its many hues, Roeg used his camera and the ambient lighting to illuminate the vivaciousness of the city and its charm by day; the closed-in buildings and frightening depths of the canals at night; and the surreal appearance of a psychic vision playing out its final moments at the end.

While in a restaurant, Laura runs into the two sisters of the story when she directs them to the restroom. Though in the telling Christine’s outfit has changed from the blue-and-white dress of the story to the red mac of the film (an important change), the blind sister again tells Laura that her little girl is sitting between her and her husband and that she is happy. When Laura enthusiastically delivers the news to John at the table, she faints with the emotion, dragging down the tablecloth with her and smashing the dishes and glassware in the process. While this may seem like an unnecessary complication to the story, Laura lying amongst the broken pieces is another bit of visual foreshadowing that Roeg adds to increase the viewers’ sense of tension.

Laura runs into the sisters again, and they warn her of impending danger, saying that the couple must leave Venice. When she tells John, however, he is outraged by the “nonsense” and refuses to give in to her pleading. The two, though, are woken in the middle of the night by a phone call from Johnnie’s school in England informing them that their son has had an accident (in the story, he has appendicitis). Laura, seeing this as the reason for the sisters’ warning, immediately makes plans to be on the next flight out of Venice to be with him, and John sees her off first thing in the morning before he returns to work at the cathedral.

John, though, has a strange experience. Traveling away from the city several hours later, he sees a small boat passing them, heading back towards it. On it are Christine, dressed in black, and the two sisters, one on either side. They don’t appear to hear him calling them, so he races back to the hotel where he assumes Laura will try to find him. The manager, though, closing the hotel for the winter season, says no one else is there, and, no, Laura has not come back. Roeg, framing John in the middle of an empty hotel lobby, its furniture already draped with sheets and dust motes floating in the air, paints a bleak picture of confusion and isolation. John goes to the police, but they are reluctant to help him with his wild stories of the two sisters’ psychic abilities and the possibility they forced Laura to come back for some devious purpose. They have a murderer on the loose, and they have more important things to do than indulge his fantasies. They do agree, though, to look into the sisters’ identities.

In the meantime, John calls his son’s school to get an update, and they – quite surprisingly – put him through to his wife, who has been there the whole time. Completely confused, John goes to the police station, where the blind sister is being held, has her released, and profusely apologizes to her for the entire mess he’s created. As he gets her back to her hotel and to her sister, though, she heads into a psychic trance; unnerved, he flees before he can hear her warning him of the danger up ahead.

As John runs through the darkened canal banks, Roeg spins the film full circle, returning to Christine and her red mac of warning. John hears a girl’s terrified cry and sees a small figure also dressed in a red mac with a hood running down the alleyway while being chased by an angry man. Roeg juxtaposes the inverted image of Christine running by the stream with the right-side-up image of this girl running by the canals’ dark waters. We feel John’s desperate desire to protect this child, as he couldn’t protect his own daughter from her fate. He continues to follow her until she finally runs into a crumbling building. “You’re safe,” he tells her, reaching out his hand. “I won’t hurt you.” But when she turns around, we see the lie. She is an old dwarf, not a child, and as she pulls the long, wicked knife out of her coat, she shakes her head at his gullibility, as she probably did for all her other victims. John realizes that when he saw Laura and the sisters in the boat, what he saw was the future, the future in which they were all coming back to Venice for his funeral. “What a bloody silly way to die …” was how du Maurier phrased his final thought.

Don’t Look Now 1973 film poster.

Non-Standard Deviations

As close as the story and the film are in many ways, there are some curious differences between the two. The first is the title. “Don’t Look Now,” according to the story, was a game John and Laura played while on holidays. They would sit at a restaurant table or stand by an attraction and glance furtively at someone near them, making up wildly fantastic stories about them, what devious plots they were hatching, and how they would be found out. This was how Laura first met the twins. She and John spied them in the restaurant, and when they went into the bathroom, Laura followed to find out more and to bring back some “juicy gossip.” The title is also relevant for the dwarf at the story’s end – John had some fantastic image of who this “child” must be and what trouble she was in and ended up paying for the misconception with his life. Why Roeg chose not to incorporate any of this is rather puzzling.

Equally puzzling is a third element of foreshadowing that du Maurier uses in the story but Roeg eliminated from the film. In the story, as Laura and John walk through the city’s deserted canal banks and alleyways at night, John hears the sound of screaming and catches a glimpse of a small girl wearing a short skirt and a pixie hood running away from someone, terrified. She disappears before John can follow her, but the image unsettles him and casts a dark pall over the crumbling buildings lining the dank waterways. This scene ties directly in to the ending of both the story and the film, so one would think it should have been a vital sequence of the latter, but it wasn’t.

Which is it to be, cinema or book.

The Final Cut

So, how did “Don’t Look Now” as a movie fare as a story adaptation overall? Roeg is a visionary director, and his artistic use of camerawork, lighting, and location did justice to the original story, even if it wasn’t an exact duplicate. The missing elements, though, do detract from the finished film somewhat, so I would give it an A-; a little more, and it would have been perfect.

What do you think? Do you agree? Disagree? Please add your comments in the section below.

– Miriam Ruff, Content Creator, PoetsIN

DISCLAIMER: The opinions discussed in this blog post are solely those of the blogger and do not necessarily represent any thoughts, values, or opinions of PoetsIN and any of its affiliate groups.

admin