This look at Snowpiercer is the next in our series of “Have You Watched a Good Book Lately?”

The series’ intention is to track a number of books’ progression from the printed page to the silver screen and assess how well or how badly the filmmakers accomplished each of the adaptations.

Will we see you at the movies, or the library?

Today we’re going to be discussing “Snowpiercer,” a French graphic novel in three parts. The first part was written by Jacques Lob (and translated into English by Virginie Selavy), with art by Jean-Marc Rochette, and it was adapted for the screen in 2013 by acclaimed Korean director Bong Joon Ho (“The Host”). For those of you unfamiliar with the basic premise, here is a brief synopsis adapted from the book and DVD covers:

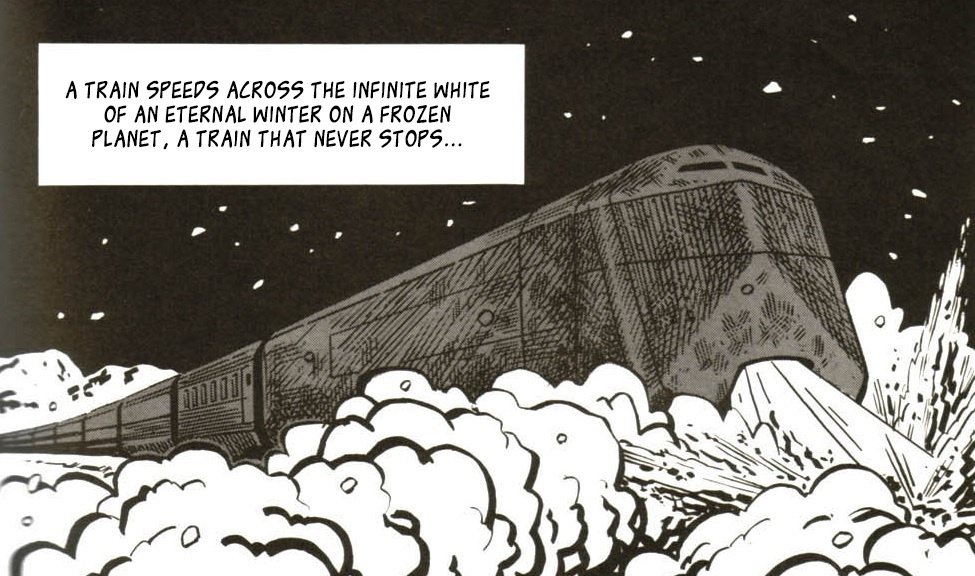

“A post-apocalyptic Ice Age has killed off nearly all life on planet Earth. All that remains of humanity are the lucky few survivors that boarded the Snowpiercer, a train that travels around the globe powered by a sacred perpetual motion engine so that it never stops on its journey. From fearsome engine to final car exists a complete hierarchy of what our society had been. The elite travel in luxury at the front of the train; those in the rear live a squalid, miserable, and short life. Now, though, a revolution is brewing, and the lower-class passengers stage an uprising, moving car-by-car toward the front of the train. But unexpected circumstances lie in wait for humanity’s tenacious survivors …”

Chris Evans as Curtis

From the Source’s Mouth

Let’s start our discussion with one of the main concerns of any book adaptation – how true is the film to the source material? Well, that’s a bit of a difficult question to answer here. There’s no question the film was based on the graphic novel: both were set in a post-apocalyptic Ice Age; both took place aboard a train that perpetually circled a ruined Earth; both had the train segregated into a hierarchical class system where it was impossible to change one’s position by moving forward, although some tried. Other than that, however, the two do not resemble each other at all.

The biggest differences are in the characters and in the plot, which is to say, the primary story elements. In the novel, the remains of humanity’s last World War board a train of 1,001 cars, the last one added at the last minute to accommodate more of the population but not supplied with food or water to keep them alive. Inexplicably, seventeen years later, a “tail-rat” named Proloff decides he wants to move up the train and takes it upon himself to make the attempt. Before he gets very far, though, he’s captured by soldiers and detained. Shortly after that, Adalaine, a young woman from third-class who’s also part of a movement to integrate the tail’s residents with the rest of the train’s population, shows up to try to get him released. She, too, is locked up. Both are accused of carrying some kind of plague, as people around them start falling ill and dying, but then they’re surprisingly ordered to be released and brought up to the front of the train where the sacred engine is housed. While there are references to others in the tail section, Proloff is the only one we really see, and he is pretty much acting alone because he’s fed up with his situation and not for any other reason. The guards are ridiculously incompetent, shooting their guns off at the slightest provocation and not caring who or what they hit, drinking copiously, and making crude remarks; and the characters are so similarly drawn that it’s difficult to tell one from the other and determine who’s saying which line. And because Proloff is gruff, rude, and totally self-absorbed, we never feel any real empathy for the person who’s supposed to be our eyes into this society.

None of this is helped by the story line, which is hampered by both bad writing and a dismal translation. Every other word is a curse word, there are lots of rat-a-tat-tats and ka-pows lettered in, and the most common phrases are “tail-rat-fucker-lover” and “HaHaHa;” these are not words to inspire a reader or make her look for any deeper meaning in the story.

The film, on the other hand, is more about the population aboard the train than any one individual. In this version, humanity attempted to seed the atmosphere with a chemical to combat global warning, but it ended up creating a perpetual Ice Age. The Snowpiercer train had already been built as a “luxury” train to ferry people around the world, but it was quickly retrofitted to house the remnants of humanity essentially until the end of time.

A page from the graphic novel

Conditions in the tail section were horrendous from the start, although Bong takes his time revealing all the details about this, building up the suspense of the complicated history with each step forward the characters make. And he doesn’t shy away from showing the dark reality of life in the back cars – we spend the first third of the film together with the tired, dirty, and sick masses huddling wall-to-wall into the tail sections, many with missing or damaged limbs. These occupants are fed solely by black, rectangular “protein bars” (which are later revealed to be made from a disgusting slurry of some kind of beetle), while the people at the front dine in lavishly spacious cars on sushi and meat and vegetables grown in special compartments. The reveal about two-thirds of the way through the film that the current situation is actually a step up for the tail’s occupants is still shocking. During the early days of the voyage, people first preyed on the weakest passengers then took to cutting off their own limbs to feed their hungry families when the supply ran out. No one stopped them.

About the only contact the front and the back of the train have are the daily head count checks, the invasive medical tests, and the occasional sweep to take away a young child, without explanation. It is from this despair that a new rebellion is born, one led by a brave and intelligent man named Curtis; the object is for a large number of the tail’s occupants to make it as far forward in the train as possible to obtain more equality and better conditions for themselves and their comrades. The decision to forge ahead is helped by a realization: The guards’ guns are essentially useless – the soldiers used up all their bullets in the previous rebellion. No bullets, no ridiculous shooting at everything, less risk of Curtis’ mob dying and a greater chance the tail section’s move will be successful. This also allows Bong to take advantage of the visual medium in which he’s working, an opportunity wasted in the graphic novel. The battles are fought hand-to-hand, with pipes, axes, and anything else heavy or sharp. These conflicts are deeply personal, and we see each blow and spatter of blood, feel each slash and crunch, sometimes just in flashes as they’re lit only by the blaze of improvised torches, needed because the train has entered a tunnel. It is all visually arresting, and it heightens our interaction with the characters and the visceral nature of the story line.

Snowpiercer

While in both the graphic novel and in the film the characters make it to the front of the train, the experiences couldn’t be more different. When Proloff is released from detention, he is taken directly to meet Alec Forrester, an engineer who developed the idea of perpetual motion. He tells Proloff that he’s dying and Proloff has to take over for him caring for the engine. We then cut to (presumably) sometime in the future where Proloff is bemoaning the fact that nothing seems to work anymore and he just wants the train to stop. End of book. A very unsatisfying conclusion.

In the film, Curtis encounters obstacle after obstacle and must fight his way (with help from others) through each gate and each checkpoint. It is only after considerable effort and loss of his friends and colleagues that he breaks his way into the sacred engine room and meets its creator, the revered Wilfred. And what he discovers there rocks the entire world he thought he knew. The stolen children are being used in place of mechanical parts of the engine that have failed, and traitors in the tail have collaborated with Wilfred to “balance” the train’s population and “prune away” those who aren’t needed. In this way, they believe, they’ll achieve a healthy, self-contained ecosystem. And since most of those pruned are from the tail, no one in the front sections questions it.

Bum son seats or book on shelf?

Non-Standard Deviations

There are a number of other differences between the graphic novel and the film, primarily in introducing new characters and developing this long-established and highly unusual society, but perhaps the most profound is in the underlying themes. As we’ve mentioned, the paucity of words in the graphic novel, and certainly in words of substance, leads to a very shallow and uninteresting story. In the film, however, Bong delves wholeheartedly into the nature of class structure, our self-created destruction of the world, the nature of friendship and betrayal, and how we respond to extreme events under pressure. These are all ideas that extend far beyond the two-hour movie, leaving the viewer contemplating how these themes relate to our own lives. That makes for a movie worth watching.

The Final Cut

So, how did “Snowpiercer” as a movie fare as a book adaptation overall? I would say that the adaptation was far superior to the source material, giving it a solid A for effort, tone, visuals, and writing.

What do you think? Do you agree? Disagree? Please add your comments in the section below.

– Miriam Ruff, Content Creator, PoetsIN

DISCLAIMER: The opinions discussed in this blog post are solely those of the blogger and do not necessarily represent any thoughts, values, or opinions of PoetsIN and any of its affiliate groups.

Please follow and like us:

This look at Snowpiercer is the next in our series of “Have You Watched a Good Book Lately?”

The series’ intention is to track a number of books’ progression from the printed page to the silver screen and assess how well or how badly the filmmakers accomplished each of the adaptations.

Will we see you at the movies, or the library?

Today we’re going to be discussing “Snowpiercer,” a French graphic novel in three parts. The first part was written by Jacques Lob (and translated into English by Virginie Selavy), with art by Jean-Marc Rochette, and it was adapted for the screen in 2013 by acclaimed Korean director Bong Joon Ho (“The Host”). For those of you unfamiliar with the basic premise, here is a brief synopsis adapted from the book and DVD covers:

“A post-apocalyptic Ice Age has killed off nearly all life on planet Earth. All that remains of humanity are the lucky few survivors that boarded the Snowpiercer, a train that travels around the globe powered by a sacred perpetual motion engine so that it never stops on its journey. From fearsome engine to final car exists a complete hierarchy of what our society had been. The elite travel in luxury at the front of the train; those in the rear live a squalid, miserable, and short life. Now, though, a revolution is brewing, and the lower-class passengers stage an uprising, moving car-by-car toward the front of the train. But unexpected circumstances lie in wait for humanity’s tenacious survivors …”

Chris Evans as Curtis

From the Source’s Mouth

Let’s start our discussion with one of the main concerns of any book adaptation – how true is the film to the source material? Well, that’s a bit of a difficult question to answer here. There’s no question the film was based on the graphic novel: both were set in a post-apocalyptic Ice Age; both took place aboard a train that perpetually circled a ruined Earth; both had the train segregated into a hierarchical class system where it was impossible to change one’s position by moving forward, although some tried. Other than that, however, the two do not resemble each other at all.

The biggest differences are in the characters and in the plot, which is to say, the primary story elements. In the novel, the remains of humanity’s last World War board a train of 1,001 cars, the last one added at the last minute to accommodate more of the population but not supplied with food or water to keep them alive. Inexplicably, seventeen years later, a “tail-rat” named Proloff decides he wants to move up the train and takes it upon himself to make the attempt. Before he gets very far, though, he’s captured by soldiers and detained. Shortly after that, Adalaine, a young woman from third-class who’s also part of a movement to integrate the tail’s residents with the rest of the train’s population, shows up to try to get him released. She, too, is locked up. Both are accused of carrying some kind of plague, as people around them start falling ill and dying, but then they’re surprisingly ordered to be released and brought up to the front of the train where the sacred engine is housed. While there are references to others in the tail section, Proloff is the only one we really see, and he is pretty much acting alone because he’s fed up with his situation and not for any other reason. The guards are ridiculously incompetent, shooting their guns off at the slightest provocation and not caring who or what they hit, drinking copiously, and making crude remarks; and the characters are so similarly drawn that it’s difficult to tell one from the other and determine who’s saying which line. And because Proloff is gruff, rude, and totally self-absorbed, we never feel any real empathy for the person who’s supposed to be our eyes into this society.

None of this is helped by the story line, which is hampered by both bad writing and a dismal translation. Every other word is a curse word, there are lots of rat-a-tat-tats and ka-pows lettered in, and the most common phrases are “tail-rat-fucker-lover” and “HaHaHa;” these are not words to inspire a reader or make her look for any deeper meaning in the story.

The film, on the other hand, is more about the population aboard the train than any one individual. In this version, humanity attempted to seed the atmosphere with a chemical to combat global warning, but it ended up creating a perpetual Ice Age. The Snowpiercer train had already been built as a “luxury” train to ferry people around the world, but it was quickly retrofitted to house the remnants of humanity essentially until the end of time.

A page from the graphic novel

Conditions in the tail section were horrendous from the start, although Bong takes his time revealing all the details about this, building up the suspense of the complicated history with each step forward the characters make. And he doesn’t shy away from showing the dark reality of life in the back cars – we spend the first third of the film together with the tired, dirty, and sick masses huddling wall-to-wall into the tail sections, many with missing or damaged limbs. These occupants are fed solely by black, rectangular “protein bars” (which are later revealed to be made from a disgusting slurry of some kind of beetle), while the people at the front dine in lavishly spacious cars on sushi and meat and vegetables grown in special compartments. The reveal about two-thirds of the way through the film that the current situation is actually a step up for the tail’s occupants is still shocking. During the early days of the voyage, people first preyed on the weakest passengers then took to cutting off their own limbs to feed their hungry families when the supply ran out. No one stopped them.

About the only contact the front and the back of the train have are the daily head count checks, the invasive medical tests, and the occasional sweep to take away a young child, without explanation. It is from this despair that a new rebellion is born, one led by a brave and intelligent man named Curtis; the object is for a large number of the tail’s occupants to make it as far forward in the train as possible to obtain more equality and better conditions for themselves and their comrades. The decision to forge ahead is helped by a realization: The guards’ guns are essentially useless – the soldiers used up all their bullets in the previous rebellion. No bullets, no ridiculous shooting at everything, less risk of Curtis’ mob dying and a greater chance the tail section’s move will be successful. This also allows Bong to take advantage of the visual medium in which he’s working, an opportunity wasted in the graphic novel. The battles are fought hand-to-hand, with pipes, axes, and anything else heavy or sharp. These conflicts are deeply personal, and we see each blow and spatter of blood, feel each slash and crunch, sometimes just in flashes as they’re lit only by the blaze of improvised torches, needed because the train has entered a tunnel. It is all visually arresting, and it heightens our interaction with the characters and the visceral nature of the story line.

Snowpiercer

While in both the graphic novel and in the film the characters make it to the front of the train, the experiences couldn’t be more different. When Proloff is released from detention, he is taken directly to meet Alec Forrester, an engineer who developed the idea of perpetual motion. He tells Proloff that he’s dying and Proloff has to take over for him caring for the engine. We then cut to (presumably) sometime in the future where Proloff is bemoaning the fact that nothing seems to work anymore and he just wants the train to stop. End of book. A very unsatisfying conclusion.

In the film, Curtis encounters obstacle after obstacle and must fight his way (with help from others) through each gate and each checkpoint. It is only after considerable effort and loss of his friends and colleagues that he breaks his way into the sacred engine room and meets its creator, the revered Wilfred. And what he discovers there rocks the entire world he thought he knew. The stolen children are being used in place of mechanical parts of the engine that have failed, and traitors in the tail have collaborated with Wilfred to “balance” the train’s population and “prune away” those who aren’t needed. In this way, they believe, they’ll achieve a healthy, self-contained ecosystem. And since most of those pruned are from the tail, no one in the front sections questions it.

Bum son seats or book on shelf?

Non-Standard Deviations

There are a number of other differences between the graphic novel and the film, primarily in introducing new characters and developing this long-established and highly unusual society, but perhaps the most profound is in the underlying themes. As we’ve mentioned, the paucity of words in the graphic novel, and certainly in words of substance, leads to a very shallow and uninteresting story. In the film, however, Bong delves wholeheartedly into the nature of class structure, our self-created destruction of the world, the nature of friendship and betrayal, and how we respond to extreme events under pressure. These are all ideas that extend far beyond the two-hour movie, leaving the viewer contemplating how these themes relate to our own lives. That makes for a movie worth watching.

The Final Cut

So, how did “Snowpiercer” as a movie fare as a book adaptation overall? I would say that the adaptation was far superior to the source material, giving it a solid A for effort, tone, visuals, and writing.

What do you think? Do you agree? Disagree? Please add your comments in the section below.

– Miriam Ruff, Content Creator, PoetsIN

DISCLAIMER: The opinions discussed in this blog post are solely those of the blogger and do not necessarily represent any thoughts, values, or opinions of PoetsIN and any of its affiliate groups.

admin